“You’re moving up to ‘Senior Chinese Railfan’ status,” Ron told me as I gathered up what I would need for my day trip to Chifeng with Zhang Zhi En. “These ‘tourists’ who only come for a week or two at a time rarely have to deal with any bureaucratic problems, but if you stay for a month or more, you usually end up making an unwanted trip to Chifeng to take care of something. And if you end up having to go all the way to Beijing, then you’ve really become a veteran.”

“You’re moving up to ‘Senior Chinese Railfan’ status,” Ron told me as I gathered up what I would need for my day trip to Chifeng with Zhang Zhi En. “These ‘tourists’ who only come for a week or two at a time rarely have to deal with any bureaucratic problems, but if you stay for a month or more, you usually end up making an unwanted trip to Chifeng to take care of something. And if you end up having to go all the way to Beijing, then you’ve really become a veteran.”My something needing attention was my wide-angle to normal zoom lens, which had suddenly developed a severe softness problem. My photos taken with it were only sharp in the center. Fortunately I noticed it very soon after it happened. It’s not the first equipment problem I’ve had here, but it is the first that’s required a special trip. I spent one day of shooting with only my telephoto zoom and quickly determined that was simply not a feasible option for the rest of this trip. Zhang Zhi En was going to Chifeng in two days to stock up on supplies for his restaurant and offered to take me with him.

I squeezed all of my 6-2 frame into the tiny front passenger seat of Zhang Zhi En’s tinier car for the three hour drive. In the back rode two women, making the trip to stock up on Amway supplies. I was quite relieved when, after we got out of Daban, Zhang Zhi En turned to me and motioned for me to put on my seatbelt, a dusty piece of faded fabric that probably hadn’t been used since his last trip to Chifeng. I gladly complied. He, on the other hand, simply pulled his belt across his chest and let it dangle loosely by his waist, having the lady sitting behind him hide the unused buckle from view. Strictly for appearances.

In Daban, along the open highway and through the small towns en route, Zhang Zhi En whipped his little car with confidence and bravado. Once in the crowded city, however, he became very cautious and timid. At one point we stopped in the middle of a wide street for apparently no reason whatsoever. It took me several seconds to realize that we were waiting for the traffic light to turn green. It was the first time a vehicle I had been riding in had actually waited at a red light in weeks.

Chifeng is a city of about half a million people along the southern border of Inner Mongolia and is the gateway for most people coming to the Ji-Tong line from Beijing. In Chifeng you can buy every spice of the Orient by the kilo out of wooden barrels. You can buy whole frozen eels from a market where the rotting fish guts pile up in buckets and lie 1/8” deep on the slippery floor. You can buy live chickens from wooden cages, real “Kentucky Fried Chicken” straight from the smiling Colonel next door, designer shoes that cost more than many Chinese make in a month or longer, and practically every point-n-shoot digicam on the market from one of the many photo finishing stores. But you can’t buy a single piece of glass with a Canon EF lens mount attached to it. Zhang Zhi En took me to one place advertising repair services, but their technician quickly decided that my autofocus zoom lens was beyond his capabilities, not in the least to my relief, for fear of voiding my warranty.

“Where did you buy your camera?” I managed to ask Zhang Zhi En in Chinese.

“Beijing!” came his quick reply.

I had a fleeting thought of asking him to take me to the train station and trying to find a ticket for the next train to Beijing, but decided against it. I tried calling Ron to ask his advice, but his cell phone wasn’t available. In the end, I returned to one of the photo stores where I bought several rolls of medium format color film to use in Ron’s Fuji rangefinder cameras, which he had brought for black & white night photography.

A day of carrying two camera bags proved cumbersome, and then we went back to the Chagganhada bridge with the film crew. The first quarter moon was hanging above it when a pair of light engines chugged across on their way back to Daban, their steam backlit in the moonlight. For all the clarity and resolution that Ron’s medium format rangefinders offered, I could never use them with their slow lenses and the slow film I found in Chifeng to take that shot, or any others like it. After the film crew packed up and went home, Ron and I had a starlit discussion about what I should do. The next afternoon, I boarded a bus in Daban to take me back to Chifeng, where I would catch an overnight train to Beijing.

At least, that was the plan. Before leaving, Ron told me, “The trains between Beijing and Chifeng are extremely popular and almost always sold-out, so buying tickets from the station is often impossible.”

Ron wasn’t coming with me on this trip, so I was completely on my own, without the crutch of his knowledge and Chinese to support me. I had grown very comfortable leaning on it.

“How then, does one buy a ticket to Beijing in Chifeng?” I asked.

“The same way you buy a steam locomotive builder’s plate in Daban,” he retorted. “Just stand around being a foreigner looking lost.”

Now that’s one thing I don’t even have to try to be good at here.

Given the circumstances, perhaps I should have been frustrated or at least considerably annoyed when I got on the bus to leave Daban, where I would lose at least two days of shooting on the Ji-Tong line, more if I wasn’t extremely lucky. I didn’t feel that way, though. After having a night to sleep on the idea (well, half a night, anyway), I was excited. This was another adventure, and I’d be completely on my own this time (save the notebook full of maps and directions Ron had meticulously prepared for me).

My trip got off to a false start when I wandered into the wrong waiting room, thinking it was the bus station and asking for a ticket. The lady inside had a good chuckle and pointed me down the street, where I found a much bigger waiting room and a ticket to Chifeng for Y35. (Upon returning, I happened to notice that the correct waiting room has a big sign out front with a picture of a bus and the English words, “Ticket buying and waiting room.”)

Chinese bus trips are a lot like Chinese meals. They start off very slowly, then, before you know it, they’re finished. The only thing more important to the Chinese than an on-time bus is a full bus. They crawl out of town, looking for any extra passengers they can pick up along the way. I was still quite tired from my big television debut, so I nodded off for most of this part. When I awoke, we were cruising through the barren mountains, golden in the late afternoon light, south of town.

What woke me was the in-flight entertainment, now in progress. On the TV monitor at the front of the bus, a woman in a long burgundy dress and a man in a sparkling red coat with the absolute highest facial features of any man I have ever seen were strutting around waiving green flags and doing something that in this country is probably considered singing. I equated the audio much more closely to pigs being slaughtered. Of course, this being China, it was being played just slightly louder than the absolute maximum volume that the speakers could handle, so the really high notes went screeching into high-pitched static before coming down again. This was followed by a movie about a cell phone that I found neither entertaining nor annoying, and for that last bit I was most grateful. However, the movie wasn’t quite long enough to get us all the way to Chifeng, so the last few dozen kilometers brought more operatic song and dance.

We arrived more than three hours before the departure of my train, so I went first to the ticket office, just in case there were any unsold berths remaining. Just before I got to the window, a man held out a ticket and said, “Beijing?”

I asked how much. “Yi bai ling yi,” Y101, which was the face value. Ron had told me some scalpers would start by asking as much as Y200, and if I could get a ticket for about Y130, I had done well. It would really depend on who was most desperate.

“Jin tian?” I queried (today?). He nodded, and I confirmed this on the ticket. I handed the man the money and took my ticket.

I still had three hours to kill, so I took a walk through town and eventually found an internet café across the street from the train station. I was feeling pretty good about myself until I realized that I hadn’t asked the man if the ticket was for sleeper class. I was exhausted and looking forward to 10 hours in a berth. The thought of spending that time in a straight-backed, non-reclining bench seat was brutal. I pulled out my Lonely Planet guidebook and looked up the Chinese character for sleeper. I began scanning the ticket and, much to my relief, found something that looked very similar.

My hopes were confirmed when the attendant for car number 8 took my ticket and handed me a plastic card for row 16, upper berth. There are two classes of Chinese sleeper trains, hard and soft. Soft class has four berths to a compartment with a locking door, plusher padding and more amenities such as reading lights. Hard class isn’t particularly hard, as the name implies, but isn’t as plush or as private as soft class. I was traveling hard class, which I had done before, but not on an overnight train.

Hard sleepers are quite the marvel of blending efficiency and comfort. I would like to think that Amtrak could make a killing with these cars (and favorable schedules for them), but they are probably a bit too communal to catch on in America. There are about 20 rows of beds per car, stacked three high. Every two rows are separated by a partition, with the two rows inside each partition facing each other. The partitions are open to the aisle and in the aisle, along the wall, two padded cushions fold down by the window to make seats for middle and upper berth passengers to sit on when they don’t feel like lying down. It is also customary for the lower berth passengers to share sitting space on their beds during the day. The lower berths have the most headroom of the three, but are also the least private. The upper berths, where I was sleeping on this trip, are a tad claustrophobic but by far the most private. They are also right next to lights, which are turned on and off by the car attendant at set times. None of that bothered me much. I fell asleep still fully dressed and without bothering to pull up the blanket before the train had even left the station.

I awoke several times during the night, stiff from the lumps in my clothes, pockets and money belt, and warm from the blanket, which, at some point, I had managed to pull around me. I was always too tired and cramped for space to get up and properly address the situation, so I arrived in Beijing feeling not quite as rested as I had hoped.

Ron had warned me that the Chifeng trains often used Beijing North Station, a small outpost in the northwest quadrant of the city several kilometers from downtown and the main station. I was feeling much more confident than I had on my first trip to the Chinese Capital, and I quickly found the subway, where Y3 and 20 minutes had me standing in front of the main railway station.

My first task was to buy a return ticket back to Chifeng, as round-trip tickets are not the order of the day in China. Like the Chifeng to Beijing tickets, these are often sold out and I might be stuck for a day unless I wanted to try an overnight bus. I found the Foreigner’s Ticket Window where the attendant spoke English. . . . and proceeded to have more trouble communicating with her than I had with all the other people on this trip who spoke only Chinese.

“Where you going?” she asked.

“Chifeng.”

“Where?”

“Chifeng.”

“Shenma?” (What?)

“Chifeng!”

“Ditu!” she begged. Luckily I knew that meant ‘map.’

I showed her on the Lonely Planet Guidebook.

“Oh! Chifeng.”

“That’s what I’ve been saying all along, dammit!” is what I wanted to shout, but instead I put on my polite smile and said, “Dui” (correct).

She had another hard sleeper ticket for Y101 available for that same night. I bought it, and walked back outside.

Being a foreigner in China and stepping out of a big-city train station reminds of the outer space video games I used to play on my cousin Matt’s Atari. It’s like that part of the game where you come out of warp speed right into the middle of the enemy space station and have to divert every bit of your available power from your main reactor to your front defense shields. It seemed like every taxi driver in China was waiting for me, and that someone had hung a big, glowing dollar sign over top of my head.

“Hullo!”

“Helloo!”

“HAH-lo!”

“Taxi!”

“You want taxi!” (said as a command, not a question)

“Binguan! I take you Binguan!”

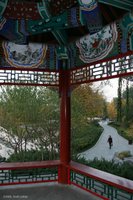

I pushed my way through the mob, head down, avoiding eye contact, and found my way back to the subway. I arrived at the camera stores an hour before they opened and set off to look for an internet café. I didn’t find one, but I did have a very pleasant walk through one of Beijing’s many hutong, narrow alleyways with small, brick huts and cottages, laundry drying in the breeze on clotheslines and rusty bicycles awaiting their next venture into the rushing streets. The hutong are part of the old way of life in Beijing, which is being phased out as quickly as possible in favor of presenting a more modern image for the 2008 Olympics, seemingly the driving force behind every construction project across the country (including the abolishment of steam). Many hutong are being lost to new developments and street-widening projects, but there are so many that not nearly all of them can be eliminated before the games. Perhaps after that, Beijing will lose some of its motivation.

I found street vendors selling fried dough/egg pancakes with a spicy sauce and baicai, China’s ubiquitous green, leafy cabbage. It was the best breakfast I have had here. I still didn’t find an internet café, even after asking a few shopkeepers, so I broke down and paid a taxi Y12 to take me to one. That’s only $1.50, but I’ve been here long enough that I’ve grown accustomed to the Chinese price structure and cringe at over-paying for anything. He even had to stop and ask for directions, but he dropped me off at the “Limitless Internet café of good luck.”

At the camera store I found a Tamron lens to fill-in for mine until I can have it repaired by Canon. I typically avoid third-party lenses, but I had heard many good reports about the new Tamron Di series for digital cameras. A quick test showed that it blew away my faulty Canon in terms of sharpness, while contrast and color didn’t look too bad, either. More importantly, it didn’t completely wreck my budget for getting to Japan next month, although I will need to get most of that money back at some point. Hopefully Canon will come through for me on the repairs. My next stop was the post office, where I boxed it up and sent it by air mail to their Irvine, CA service center.

It was noon and I was starved from all the walking. The post office was on a busy street filled with office buildings and no restaurants, but in Beijing I have discovered that a quick turn into almost any side street will at least find you something to eat.

The first sign I saw was in English, and it even looked English – The John Bull Pub. I kept walking. Then I stopped and turned around. After seven weeks of eating nothing but Chinese, I was due for a break. The lunch crowd was thin but the place had a warm, home-like feeling to it with well-decorate wood walls, wooden tables and floors. The waitress was Chinese but she spoke English fairly well and brought me a menu that had not one, single Chinese character anywhere on it. I turned to the entries and ordered spaghetti and meatballs.

With all my errands complete, I had the afternoon free for site-seeing. I opened my guidebook and began looking for nearby attractions. The China Art Gallery was only a couple of kilometers away. It was a nice day for November and I would have preferred something outside, but I kept coming back to the art gallery. The entrance fee of Y20 was five times more than the book had advertised, but I paid my money and walked inside.

The main exhibit was Chinese calligraphy. I know the Chinese consider it very beautiful and that I should be able to appreciate it even without knowing how to read it, but the black brush strokes on long white scrolls just couldn’t hold my attention. I wandered into a side hall where I saw some paintings. The first one was a beautiful portrait of some colorful old men in a mountainous landscape and -- yes, I believe that’s a railroad bridge in the background! The next featured a herdsman with his yaks and again, far in the distance, a railroad bridge. Then I found a painting of a young boy and his grandfather gazing out across dark mountains into a rainbow, where a railroad bridge with a train followed the colorful arc across the valley. The room was filled with similar paintings – fabulous landscapes and haunting portraits, all with a hint of a railway somewhere in the background. In one, a mother held her young son up in the air while their dog sat at her feet, their yaks roamed the grasslands behind them, and far beyond, on one side of them a railway bridge, and on the other side, construction equipment working on more of the line. On the floor below this painting, a young Chinese boy sat with his sketch book spread out on a folding stool and copied the scene with his pencil in impressive detail.

I lingered for some time in the room, spellbound by the faces in the portraits looking back at me and this railway being built beyond them. Some seemed to smile, but others were betrayed by eyes clearly questioning the coming of this new technology to their way of life. Finally I realized the exhibit was a feature on the construction of the new railway line to Tibet. I walked into the next room and was thrilled to find the exhibit continued through it and on into yet another room. Copies of “China Railway Construction News” were available at a table in the last room, with several of the paintings reproduced in newsprint. The exhibit must be sanctioned, or at least approved, by the railway, and indeed many of the paintings presented it in a very positive light, and yet there were those eyes in a few. One in particular stays with me. A mother with a baby on her back walks along the tracks where a flatcar sits carrying a cast concrete bridge span while construction crews work on the bridge in the distance. Beside the mother stands her half-grown son in a fur coat, looking back, looking straight into me with bigger-than-life brown eyes that seem to cry “my way of life is forever passing with the coming of this new thing.”

I can’t read the titles or the captions or even the artists’ names, but I can read that boy’s eyes. I’m glad for them. I’m glad for all the paintings, which seem to so richly express the mixed feelings I have about the impact of the trains I love on the land and the people around them. I’m glad the Chinese government didn’t censor that painting and the others that seem to call some questioning towards the new railway. And I’m so glad I found that exhibit. Seeing it alone was worth the trip to Beijing.

I found a quiet park behind the Forbidden City, then watched the lowering of the flag in Tiananmen Square. I found dinner, called Ron, took night photos with my new lens and eventually found my way back to Beijing North Train Station.

“Do you speak English?” asked the young Chinese woman in front of me with a hopeful smile as we boarded the train to Chifeng.

“Yes!” I replied, taken by surprise. It was the first time anyone in China had asked me if I spoke English. “Much better than I speak Chinese.”

“Good! I love meeting foreigners.”

“Probably so you can practice your English,” I was thinking, when she added, with a half-apologetic look, “I like to practice my English.”

I had been up since 4:30, so I explained that I was very tired and anxious to get to sleep as I climbed into my upper berth, which was in the compartment next to hers. She found me a few minutes later.

“Please come down.”

“I’m so tired.”

Still she waited hopefully in the aisle, so I turned around (a difficult process for a person of my size in the upper berth of a hard sleeper) to face her with the hopes that a few moments of chatting would appease her.

We exchanged names. Hers was Arabella.

“That’s a very pretty name!”

“Everybody likes my name! I don’t understand, though, because it is very hard to pronounce.”

“It isn’t hard for me, but for Chinese people it must be very difficult.”

“My neck is hurting from looking up at you,” she said.

I looked around. The lights were shining brightly, music was playing on the speakers, everyone was talking and there I was no way I could get to sleep right now. So I came down. She offered me a seat beside her on her lower berth.

“You’re easy to talk to,” she said. “You smiled and said ‘hello’ when I spoke to you. I say ‘hi’ to many foreigners, but most just turn away.”

“So many Chinese try to sell things to foreigners that we often just stop responding. It’s very frustrating when everyone is trying to get you to buy something.”

We passed the dark miles with the kind of small talk that I so often avoid at social gatherings. Yet here it was strangely refreshing. The train staff turned off the lights at 10:30 and I took my leave to my berth. Arabella only let me go when I promised to talk with her again in the morning before the train arrived.

I slept deeply, and when the lights came on at 6:00, considered just staying under the bedding with my eyes closed. Something drew me out, though, and I rubbed the sleep from my still-tired eyes and found the bathroom where I brushed my teeth beside a young Chinese man. His tight black shirt was clean and crisp and he laboriously combed, smoothed and re-combed his ebony-silk hair. I wondered how many days had passed since a comb had passed over my own head.

I found Arabella sitting up in her berth, looking like she had been expecting me all morning. She asked what I did and I told her I was a writer (so much simpler than explaining my complete situation) and that I was on my way to Japan where I would join my fiancé.

“Are you married?”

“No,” she said, shaking her head. “I’m single.” Then she added with a hint of embarassment, “To tell the truth, I am divorced. Do you think it’s bad to be divorved?”

I paused. “No, I don’t. My parents are divorced and remarried and are much happier now. Maureen’s parents are also divorced, and they are much happier, too. It’s made us cautious, though. We waited longer than many couples do to get engaged.”

“Do you mind talking about this with me?” she asked. “Many Chinese avoid such subjects, but I don’t mind.”

“I don’t mind, either.”

In Chifeng she walked me to the bus station and helped me find a ticket for the very next bus, which was leaving in 15 minutes. She found a taxi to take her to her job, which started in less than an hour.

“How do you say good-bye in America?” she asked.

“Well, many people shake hands and say good-bye, and sometimes good friends will hug each other.” Then I added, “If it’s okay with you, I’d like to give you a hug.”

“Yes. I could use a hug.”

“So could I.”

As I settled into my seat for the three hour ride back to Daban, I wondered how many weeks had passed since my last hug. Too many. I gazed out the windows over the factory smokestacks to the sun-parched hills on the horizon and counted the days until I would see Maureen again. I was feeling quite wistful and contemplative until the TV monitor came on. It was the exact same programming we’d had for the trip down.

Where are those earplugs?

3 comments:

Great story. I would love to be where you are. I spent a year in China in 1998-99 in Anhui Province teaching English.

I also love trains and photography. It sounds like you are having a great adventure. Best Wishes and Safety.

Good to read the happy end of your Beijing adventure. During my two days stay in Beijing after our common Jitong trip I also met very nice people, even I drove the town alone on a old bicycle. I enjoyed visiting the same park up on the coal hill north to the Emperors Palace. An old boxer and his friend, looking like a criminal, invited me to drink a beer together. They offered a prostitute to me. Believe me, I was very lucky to go to my bed in an old Hutong quarter. I hope you will be pleased with your new lens. If it's the 28-75, I use the same one and I'm very happy with it.

Take care, Olaf

Scott,

I knew I should have left a bunch of cards with you to hand out to lonely China girls.....

Post a Comment